The Pre-History of Science Fiction

What do our dreams say about us?

Nothing, some claim; they’re a series of random images jumbled together by our unconscious minds. Others believe that some of them, at least, have a deeper meaning; they’re our subconscious, trying to tell us something important. Or, perhaps just that we left the front door unlocked.

For most of human history, however, dreams have been considered extremely important. In many cultures they were (and are) considered messages from God, or the gods, or “the other side.” In mythology, dreams serve as portents of future events: warnings, or occasionally, something more sinister. In the Iliad, Zeus sends the Mycenaean king Agamemnon a false dream, in which he indicates that the city of Troy will easily fall if the Greeks unite to attack it. “So spake the Dream,” Homer writes, “and departed and left him there, deeming in his mind things that were not to be fulfilled.” Agamemnon trusts the dream, and commits to the war, and the sorrows of Greeks and Trojans follow.

In literature, dreams often reveal the secret fears and desires of characters. Shakespeare uses dreams for this effect in his plays. In The Tempest, Caliban tells his co-conspirators of a dream in which “The clouds methought would open and show riches / Ready to drop upon me, that when I waked / I cried to dream again.” Hamlet speaks often of dreams, and Macbeth is undone, in part, by one.

Then there is the fact that the word “dream,” in English at least, has two meanings. There are the dreams we have while we’re asleep, and there are the ones we shout in the streets, or carry silently in our hearts. Whether we strive to make them a reality, or whether they drive us forward, unattainable. Whether they’ve already died — or whether we tell ourselves they have, so we don’t feel as bad for giving up on them.

The two ideas have always been linked in our minds. In some way we have always believed what Shakespeare and other writers have: that our dreams and our hopes, desires, and fears are one and the same. And if that’s true of individuals, then what about our dreams? The ones we as groups, as cultures, even as a species share? What do they say about us? And how do we figure out what they are?

One way is by looking at the stories we tell each other. We humans are a race of storytellers. It’s one of the few things that makes us truly different from other animals, the way that we use representational language to transmit information from one person, from one generation to another. It started eons ago with the simplest of similes, used to teach hunting tactics or warn about dangerous areas. And it’s grown in complexity over the millennia, until now we have novels, films, video games, all geared toward that purpose. In many ways, our whole civilization is built around stories. Deep in our genes, we yearn to sit around a fire, listen to a friend tell a tale, and find the truth in its fiction.

So let’s do that together now, as we explore the history of my favorite genre of story — science fiction.

THE NATURE OF THE BEAST

What exactly is science fiction? You can find definitions in dictionaries, Wikipedia… blogs. If you’re reading this, I’m sure you have your own; maybe something that incorporates what these stories have meant to you personally.

For myself, I’m not sure that I had a strong one before I started writing this. If you had asked me to spell it out on any given day, I might have given you a different answer. Partially that’s because it’s such a versatile genre, but I think it’s also that sci-fi has been an important part of my life for so long, I took for granted that I knew what it was. And when I decided to write a series on its early history, I took for granted that I knew what the first true sci-fi story was. I found out that I was wrong. And on the journey to that discovery, I formed a more coherent picture of what the genre is, at least to me.

That journey starts far earlier than I thought it did. So let’s go all the way back to that starting point: the oldest thing I could find that bears a resemblance to the science fiction stories we know and love today.

THE RAMAYANA & THE MAHABHARATA

Around two and a half thousand years ago, in what is today India, someone started writing an epic poem. This person we call Valmiki, a name given to a legendary figure referred to as the Adi Kavi, or first poet. The work he began writing sometime between 700 and 500 BCE — the Ramayana — would be called the first poem. And it would be one of the foundational texts of Hinduism.

It tells the story of a prince named Rama, the 7th avatar of the god Vishnu. After Rama is exiled from his home kingdom of Kosala, he travels around the India of the Treta Yuga, or Second Age of Man. Which, depending on the count, may have ended as many as three million years ago. Rama’s journey tells the story of that unfathomably ancient land, and in so doing, tells the reader something about the India of Valmiki’s day — or perhaps, India as it should have been, as idealists hoped it could be.

Like most religious texts, the Ramayana depicts ideals of social roles, political forms, philosophy. It uses its characters’ hardships and triumphs to teach moral lessons to the reader. It also depicts magical abilities, gods and divine creatures, things which would inspire works of fantasy fiction for millennia afterward. But it also contains depictions of things which would be familiar to any science fiction fan in the 21st century.

In the course of his travels, Rama’s wife Sita — daughter of Mother Earth and avatara of the goddess Lakshmi — is kidnapped by a rival king. To free her, Rama must wage war against this hostile kingdom. As he is favored of the gods, he receives their aid in the form of divine weapons called Brahmastra, or Brahmashira, so called because they were forged by Brahma, the creator-god aspect of Vishnu.

But these gifts are not given lightly. As Vishnu is bestowing such a weapon upon Rama, he warns the prince that “the weapon called brahmashira… is capable of consuming the whole world”, and that “Even when overtaken by the greatest danger, O child in the midst of battle, thou shouldst never use this weapon, particularly against human beings”. For these weapons were crafted to kill gods — and are the only things in the universe capable of doing so.

As an example of their power, at one point Rama is attempting to storm an enemy castle, from which he’s separated by a vast ocean. Lacking boats, he decides to use a Brahmastra to blast a path through the sea for his troops. Before he can fire it, the god appears before him and bids him to stop, lest he destroy the whole ocean. He promises to carry Rama and his troops to their destination instead. But once a Brahmastra has been drawn, it must be fired. So Rama shoots it into the air; it comes down in a lush valley called Rajistan, and explodes with such force that it turns the entire area into a desert, which it remains to this day.

One of the interesting things about these Brahmastra is that they are described as weapons — not magical or divine abilities, but objects that a mortal can pick up and use as they would a bow and arrow. Imbued with divine power, of course, but physical, and mechanical. These weapons would also appear in the Mahabharata, a later epic poem of similar cultural importance. This work covers a long dynastic struggle between two related clans, the Kaurava and the Pandava, at the end of the Dvapara Yuga, or Third Age of Man. The conflict turns family against family in a tragic bloodbath, culminating in the eighteen day Kurukshetra War.

Millions die in this short span of days, owing to the use of Brahma weapons as the violence spirals out of control, each side driven to a frenzy to avenge the loved ones lost in the struggle. The war is part of the descent of man into the Fourth and final age, the Kali Yuga — our own time, when cruelty and corruption reign, and humanity reaches its lowest state before the world ends, and the cycle of ages begins anew.

These Brahmastra have been compared to nuclear weapons, and understandably so — even to the extent that some fringe theorists believe these stories may be based on accounts of actual nuclear weapons, either used by lost advanced human civilizations of the distant past, or, of course… by ancient aliens.

These epics, and earlier Rigvedic poems, are also believed to contain the first examples in human literature of ‘flying machines’ — again, distinct from the flying chariots or horses gods are depicted riding in other texts. In some cases they’re mechanical birds, in others levitating cities, capable of flying around the world by harnessing the power of “fire and water.”

To complete the sci-fi trifecta, there’s even a section in the Mahabharata in which King Raivata travels to the divine realm to consult with Brahma about a husband for his daughter. Though he’s there only for a few days, when he returns to Earth centuries, or even millennia, have passed, so long that he finds “the race of men dwindled in stature, reduced in vigor, and enfeebled in intellect,” which may be the first reference in human literature to time travel, or at least the relative nature of time.

The question is this: as stunning as the imagination of these poets was, can we really call what they wrote science fiction? Certainly, the poems contain many genre elements, but to call them that would be wrong. Partially because these ideas aren’t based on science — science didn’t exist when they were written — and partially because these poems, ultimately, are not fiction. They’re religious texts. As such, they fulfill a much different purpose than sci-fi literature does today. They’re not meant to entertain, nor to speculate on the future. They may do those things, but it’s not their purpose. They’re meant to educate, and to tell us something about ourselves, to teach us how to live in accordance with the values of the culture and time that produced them.

Of course, science fiction stories can do those things, and mean a great deal to people. Nobody knows that better than me; but rarely if ever can they hold as much importance as a person’s religious faith. And even if they do, it’s not their purpose.

One thing that strikes me about these texts is the astonishing depth of imagination at work in them. Valmiki never saw a flying city; he never saw a nuclear weapon. The authors of the Rigvedic poems never saw airplanes in flight. Vyasa, the legendary author of the Mahabharata, never traveled through time. Yet they were able to imagine these things, and describe them clearly and evocatively, two thousand years before anything like them would be invented, or even theorized by science. Imagination is that peculiarly human ability that allows us to reach outside our experience, and touch the vast worlds beyond.

TRUE HISTORY

And imagination is something the next work on our list has in spades. It was written in the 2nd century CE, in the Roman province of Syria, by Lucian of Samosata. He was a writer, a satirist, and rhetorician — meaning he taught people how to argue, which might give some clue as to his personality. He relentlessly mocked public figures, other writers, and superstition in his works. And he was extremely sarcastic, so much so that we can’t be certain of any of the details he tells us about his life. He was a bit like a 2nd century Stephen Colbert, of the Report era, in that respect, never breaking character, and ripping his targets (himself included) to shreds.

His cheekily titled True History describes Lucian and a coterie of friends going on an impossible journey around, and beyond, the world. Among other places, they travel to the moon in a boat, where they become involved in an interplanetary war. Apparently the King of the Moon, Endymion, and the King of the Sun, Phaethon, are in dispute over colonization rights to the Morning Star, what we today call the planet Venus. Lucian and his friends join forces with Endymion, and take part in a battle of divine scale, with millions of soldiers on each side. The Moonites deploy giant space spiders, countered by the Sunites’ giant space ants. The titanic battle is ultimately decided when the Sunites erect a wall of clouds to block off the moon from the sun’s light. The Moonites are forced to surrender, and relinquish the rights to Venus for all time.

Now, space empires squabbling over planets is a plot device familiar to any modern science fiction fan, and here it is appearing in a work of fiction almost two thousand years old. The fact that True History is a satire doesn’t necessarily exclude it from the genre; some of the most memorable sci-fi stories have been comedic or satirical in nature, as anyone who’s read Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy can tell you.

But again, I think we need to look at the purpose behind the writing. Lucian’s intent was to roast ancient historians and biographers who related the impossible as if it were fact. After the Moon-Sun War, Lucian and his companions return to Earth and visit more fantastical locations. One such place is an island, upon which the great villains of history are tortured for eternity. According to Lucian: “the severest torments were reserved for those who in life had been liars and written false history; the class was numerous, and included Ctesias of Cnidus, and Herodotus. The fact was an encouragement to me, knowing that I had never told a lie.”

Which, of course, was a lie, and his readers knew it. That was the point. Lucian seemed to take particular pleasure in skewering the then long-dead Herodotus, the Father of History, who related impossible numbers in the millions for the Persian armies at the battle of Thermopylae, and told with perfect seriousness of the giant intelligent ants that mined gold in Southern Egypt. Lucian states his purpose explicitly at the beginning of True History: “When I come across a writer of this sort, I don’t much mind his lying; the practice is far too well established, even with professed philosophers. I am only surprised at his supposition that nobody would notice he was lying.”

And this, I think, is something that makes True History distinct from true sci-fi. The characters explore strange new worlds, meet new life and new civilizations, and boldly if sarcastically go where no human had gone before. But Lucian doesn’t believe any of these things are actually possible, or ever will be. He specifically chooses to write about them because they’re impossible. If anything, True History is a parody of the fantastical. The novelist Kingsley Amis wrote that True History reads “like a joke at the expense of nearly all early-modern science fiction,” yet written centuries before those works. And how can the first work in a genre be a parody of that genre?

That’s of course aside from the fact that, like the Ramayana, True History predates science as a discipline. At that time, the study of the world was called natural philosophy. While some of the principles which would later inform the Scientific Revolution were known at this time, there was no coherent system with which to apply them. And, as in the next works we’re going to look at, science and superstition were often one and the same.

1001 NIGHTS

Jumping forward another thousand years or so, we find a classic I’m sure most of you are familiar with. Compiled during the Islamic Golden Age, coinciding roughly with the European Middle Ages, the 1001 Nights is a collection of Arabic folk tales and stories, united by an ingenious frame narrative. A woman, Scheherazade, is telling the stories to her new husband to keep him from murdering her the morning after he’s had his way with her, in a somewhat self-defeating method of ensuring her fidelity.

Most of the stories are fantasy, allegory, or even discussions of mathematics or Islamic philosophy. But a few contain conspicuous sci-fi elements. In one, The Ebony Horse, the King of Persia holds a festival, during which he is approached by three wise men of different countries, “cunning artificers… versed in the knowledge of occult truths.” The Indian artificer presents a golden statue of a man, which is in fact an automaton capable of guarding the palace. The Greek artificer presents a… peacock clock that eats its own young for some reason. And the Persian artificer presents the title object: a black, wooden horse capable of flight.

The artificer promises it can “cover the distance on foot of a year in a single day.” The king is smitten by the mechanical wonder, and promises his daughter’s hand in marriage to the artificer in exchange. When the princess finds out, she’s less than thrilled about the prospect of marrying the wizened, leering old man. She tells her brother, who goes to confront the artificer. But the cunning old fellow tricks the prince into getting on the horse, and shows him only the controls for lift. The prince promptly shoots off into the sky, with no idea how to get back down.

Ultimately, he figures out the various knobs and dials on the machine, and descends back to earth. Fortunately for him, he meets there a beautiful princess in a faraway kingdom. He flies back home on the horse to reveal the artificer’s treachery. The old man is carted away to be imprisoned, and his intended bride is saved from the indignity of being married to him (a lesson which was evidently lost on poor Scheherazade’s husband, as the stories must continue the following night). The prince marries the foreign princess, and everyone lives happily ever after. Except the horse, which is burned for being the product of witchcraft.

Therein lies the confusion I was referencing earlier. The horse is clearly a flying machine. It’s even controlled by… controls, not incantations or spells. Its creator is referred to as an artificer, an inventor — but also as a wizard, and a necromancer, presumably for his ability to bring “dead” wood to life. Creators of automatons and similar devices in medieval European literature are also often referred to as necromancers, showing the conflation between science, philosophy, and magic in this era, even in the more learned Islamic world of the Golden Age.

The same is true in another story, The City of Brass, in which the Caliph of Syria sends an expedition to discover the lost city of King Solomon. The explorers discover the city, which is protected both by magical incantations — defeated by prayer to Allah — and mechanical men, which must be outsmarted or evaded.

This story also shows another key component of pre-modern ideas about the world. As in the cyclical belief system of Hinduism, the generally accepted view was that humanity’s best days were behind us. The distant past was almost always a golden age, when gods walked among men, and we built things of such wonder as would never be seen again. And this belief wouldn’t fundamentally change until the Scientific Revolution — until we started to learn things that humanity had never before known. Answer questions we hadn’t even known to ask. And start to imagine a future in which those answers might give us things we had only ever dreamed of.

SOMNIUM

Of the many lights of the early Scientific Revolution, few shone more brightly than Johannes Kepler. A mathematician and astronomer / astrologer — for there was then no distinction between the two disciplines — Kepler was the first person to draft laws of planetary motion. In the early 17th century, physics was a branch of natural philosophy, and concerned itself only with terrestrial matters. When he created his laws, Kepler also founded an entirely new discipline, which he called “celestial physics.” Today, we call it astrophysics. Had he done nothing else, that alone would make him one of the most important pioneers in the history of science.

But he did far more than that. In addition to other mathematical and scientific achievements, between 1608 and 1611 he wrote a novella called Somnium — The Dream. Like True History before it, Somnium describes a journey to the moon. Kepler’s original intent in writing it was to defend the heliocentric theories of Copernicus. These were considered heretical by the Church, and in fact rejected by Kepler’s own mentor, Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, a man famous both for his scientific discoveries and for getting his nose cut off in a drunken duel with his cousin.

As Kepler wrote Somnium, however, it became something much more than a mere scientific apologia. The story opens with Kepler narrating in first person. He describes himself reading about the legends of Bohemia, where he then worked as Imperial Mathematician to the Holy Roman Emperor. In particular, he reads one legend about an ancient queen and magician named Libussa. He falls asleep reading, and begins to dream. In the dream, he’s… also reading a book. This book contains the actual story.

The dream-book is the first hand account of an Icelandic astronomer named Duracotus. He begins by describing his homeland, the unusual day-night cycles in that far northern part of the world, and how they’re caused by the motion of the Earth around the sun. He then describes his childhood; his mother, Floxhilde, was an herbalist. When he was young, she left him on a ship as punishment for ruining an herbal bag she was selling to its captain. The ship left before she could retrieve him, and took him to Denmark, where Duracotus spent the next few years as an apprentice to the astronomer, Tycho Brahe.

Duracotus learns mathematics and astronomy from Brahe, then returns home to Iceland to practice as a scientist. And, to let his mother know he hadn’t died on that ship all those years ago. His mother is thrilled to see him, and delighted at his new scientific knowledge. Floxhilde herself is a pagan and occultist, and keenly interested in the natural world, an interest they now share in common. She tells her son of a gentle spirit she’s capable of summoning, which has the power to transport them anywhere in the universe. She wants to summon it so it can take them to the moon, which it calls Levania, so Duracotus can see up close what he’s been studying through a telescope for years.

<s>Kepler</s> Duracotus accepts the offer, and the spirit is summoned. It describes for them the journey, and what they’ll encounter when they arrive. It’s here that the most obvious parallels to modern science fiction begin. Kepler houses within this magical frame narrative all the current scientific knowledge he can about the moon and planets, as well as some fascinating speculation based on that knowledge.

The spirit says that the traveler first “experiences a strong pressure, not unlike an explosion of gunpowder, as he is hurled above the mountains and the seas.” Those so transported must be unconscious, and lie flat so they are not crushed by the massive forces exerted upon them. The aether — outer space — through which they must travel is freezing cold and devoid of air. As such the travelers must be wrapped in warm blankets, and have damp sponges placed over their mouth and nose, which will help them breathe somehow.

At the halfway point, the force lifts, and the body falls toward the moon of its own accord. But that’s a bit slow, so the spirit will speed them up, then rush on ahead to the moon’s surface to catch them before impact. The journey must be made during the lunar night, for the spirit and others of his kind must always remain in Earth’s shadow, as sunlight is damaging to them. This is particularly notable because Kepler was in fact the first to theorize that the Earth, if seen from the surface of the moon, would be capable of eclipsing the sun.

The spirit describes the other native inhabitants of the moon: giants who live only on the side facing the Earth, “forever blessed” by its reflected light. The far side of the moon is inhabited by a race of snake-like beings who build towns, farms, and cities not unlike those on Earth. Each of these races come out only during the lunar day, and hide underground for warmth during the freezing lunar night. A network of underground canals pumps water from one side to the other, always keeping it on the side facing the sun, to prevent it freezing and ensure both species can make use of it.

This may be the first example in literature of an author trying to imagine what the inhabitants of another world would actually be like, using scientific knowledge of their environment to inform that picture. The more famous first example is HG Wells’ Martians in The War of the Worlds — but Somnium predates that work, and the theory of evolution, by more than two hundred years, making the imagination of its author all the more spectacular.

Midway through this fascinating depiction, the original narrator, Kepler, is awakened from his dream by a storm. He finds that he is wrapped in blankets, just like Duracotus and Floxhilde would have been before they began their journey. And thus, Somnium ends.

If it were nothing more than a vehicle for Kepler’s scientific observations and speculations, it would be interesting enough. But there’s more to it than that. In the book within a dream within a book, Duracotus says that the events he’s about to describe happened long ago. He wanted to tell the story sooner, but he wouldn’t do it while his mother was alive. Floxhilde after all was a pagan, and practiced what the Church would consider witchcraft. If the story had become known while she lived, she would have been persecuted, and possibly killed.

Duracotus is clearly a stand-in for Kepler — also an astronomer, also a student of Brahe. And Floxhilde is a stand-in for Kepler’s mother, Katharina. She too was an herbalist, and may have engaged in pagan practices. Like Duracotus, Kepler never actually published Somnium; it wouldn’t be published until 1634, two years after his death. The multiple levels of frame narrative may be a symbolic way of removing him, and thus his mother, from the story’s heretical elements. He feared it might be used against her.

And despite his efforts, it was. In 1615, Katharina was arrested and accused of witchcraft in the German town of Leonberg, not far from her native Stuttgart. Kepler managed to get her released, but when she returned in 1620 she was arrested again. By that time, the brutal conflict that would become the Thirty Years War was raging in the Holy Roman Empire, which included modern Germany. A wave of religious violence and paranoia was sweeping Europe; Katharina was threatened with torture, but refused to confess. Again, Kepler came to her defense. Apparently, the unpublished manuscript of Somnium, which the prosecution had somehow obtained, was used as evidence against her.

Fortunately, Kepler again secured her release, but only after fourteen months of imprisonment. She died the following year, at the age of 76. Kepler was a religious man. He believed that the laws of nature had been left by God “within the grasp of the human mind; God wanted us to recognize them by creating us after his own image so that we could share in his own thoughts.” But he also loved his mother, and defended her right to her beliefs.

And it’s clear he chafed against the myopia and religious bigotry of the Church. Early in Somnium, Duracotus relates something Floxhilde told him, something it’s easy to imagine Katharina saying to Johannes: “Indeed, she said, there were many evil people who hated any arts their dull minds could not grasp — so they misrepresented those arts and made laws harmful to the human race.”

So here in Somnium we see all the elements we might expect to find in good science fiction today: science, speculation, social critique, and an emotional core holding it all together. And while the story describes traveling to the moon by magical means, unlike Lucian, Kepler did believe it might one day be possible for humans to go there using science.

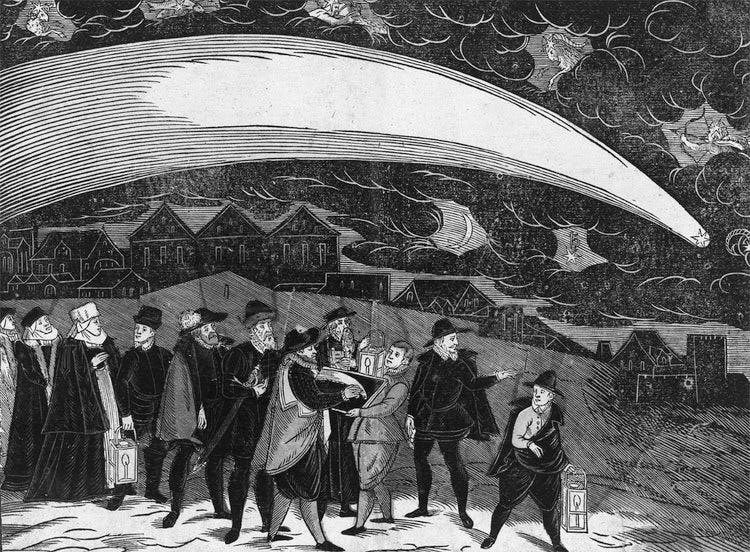

In fact, Kepler was the first to theorize, watching Halley’s comet in 1607, that the sun’s rays were heating the ice ball up, vaporizing parts of it which became its distinctive tail. He further theorized, based on this interaction between light and a physical object, that a sail might one day be constructed which could harness that force as contemporary sails harnessed the wind. In a 1608 letter to Galileo, he wrote, “Provide ships or sails adapted to the heavenly breezes, and there will be some who will brave even that void,” anticipating both spacecraft and the courage of the men and women that would crew them by more than three centuries.

THE DREAM

When I read the synopsis of Somnium, I expected to find it a dry but interesting exploration of 17th century knowledge of the cosmos. Instead I found it poignant, and ultimately inspiring, a story that I think should be recognized as the very first true science fiction tale ever written. I’m not the first person to suggest that of course — no less than Carl Sagan was one of the champions of that idea, and he spoke about it in a moving segment of his show Cosmos in the 1970’s.

What’s inspiring about it is that Kepler’s dream is still with us today. It’s been with us since the dawn of science; a dream that the future could be not only different, but better. That we could improve our society and ourselves, that we could one day travel the stars, and live in a world that had moved beyond the kind of ignorance and prejudice that Katharina Kepler had to face.

It’s a hope shared by people all over the world. One of the earliest memories I have is sitting in a train with my parents, reading a picture book about the solar system. I was perhaps 5 or 6, and I remember looking at these simplistic pictures of Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Mars — the same planets Kepler watched through his telescope. They were the most awesome things I had ever seen. I marveled at them, in that way only a 5 year old can. And I knew right away, in fact I told my mother right then, that someday I wanted to go there. I wanted to see the planets and the stars up close, with my own eyes.

That was my very first dream. It led me to devour Star Trek and Star Wars as soon as I was old enough. I read the books, bought the figures, played out my own little episodes with my friends, and wrote fully illustrated fan fiction, which I proudly showed off in class every chance I got. I also decided, like a lot of kids, that I wanted to be an astronaut, probably about five minutes after learning what an astronaut was. I held onto that version of the dream right up until the age that I realized you needed to be really good at math and science to become one, and that I… was not.

Something in that dream was stubborn, though. It refused to let a little thing like reality get in the way — even once I grew up and realized that, for a lot of reasons, I probably wouldn’t live to see that future I’d hoped for, where humanity reached out for the stars with joined hands. But that doesn’t mean that dream died. It just evolved. I realized that maybe I would never live that dream in reality, but by writing about it, I could live it in my mind. Kepler knew he would certainly never see it in his lifetime, but that didn’t stop him from dreaming. And it doesn’t need to stop us.

That’s what science fiction is, I think. Our dreams. And whatever else you can say about dreams, they all have one thing in common.

They tell us who we are.

THE NIGHTMARE

But… Dreams aren’t always positive; not always shining beacons, guiding us toward the future we aspire to. There are nightmares, too. Of what we hope desperately to avoid. Of what we fear we might become. And these, too, tell us who we are.

If Kepler is the father of the bright, aspirational half of science fiction, then the author we’re going to discuss next is the mother of that nightmarish, darker half. Or, maybe not its mother; maybe the mad genius who stitched it together from disparate parts, brought it screaming and grasping into the world with a spark of unholy inspiration, to peer through milky eyes at its creator and ask in a rasping voice… “What am I?”

Being an avid Science Fiction fan since early child hood and having read literally thousands of books in my (long) lifetime I was enthralled by your 'Pre-History of Science Fiction'. Whilst I have never heard of most of your references, let alone read them, it made we want to look each of these out and read them for myself, perhaps with your insight in to them in mind while I read.

I did read '1001 nights' as a young reader and was enthralled by each and every tale, living in my mind each of them as though I was in the story (I have always had a great imagination).

Thank you for your Substack on this subject, I was and am totally absorbed by it.

Deepest regards

Ken Gladwin